"British Rail did not name any locomotives at all between the beginning of 1967 and the end of 1975. That's nine full years without any namings. Just let that sink in for a moment. Nine years."

Onto its second name... 86229 was originally named Sir John Betjeman in mid 1983. It was renamed Lions Clubs International whilst with Virgin West Coast fifteen years later. This shot shows the loco at Birmingham New Street on 15th November 2001.

If we're talking about classic diesel traction and I refer to Merddin Emrys, do I mean 47281, or do I mean 47145? If I reference Petrolea, do I mean 47374, or 37888, or 58042?... Unless we already have a context, you won't know. That's because these example names appeared on all of the loco options I've cited. Over the years, locomotive and train names have been fairly casually recyclable, or transient in their association with particular items of stock. Does that defeat the point of naming?

What, indeed, even is the point of naming? Who or what is it for? Is it for the rail enthusiast? For the wider public? For the person, group or entity honoured in the name? Or is it for the media, and ultimately for the publicity benefit of the train operator? Is naming about respect? And if so, does that respect extend to the actual loco or train? Is it about schmoozing? Is it about virtue signalling? Is it merely an honest attempt to add kudos to rail travel?... It would be naive to think it's not to some extent about the train operator drawing attention to itself. But has that quest, at times, been a little too obvious?...

Many of the 'namers' from the 1960s were lost through the early withdrawal of the locomotives. The Western Region's 'Warship' class was a memory by the mid 1970s, and the 'Westerns' - also named - soon followed the 'Warships' to the scrapyard. 'Warship' D821 Greyhound was saved and entered preservation.

What we can say for definite, is that attitudes towards naming have changed over the years. And the outcome has not always been one of universal content.

The general flippancy and transience of naming, which increased enormously between the 1960s and the 1990s, has not only soured a few faces during the service lives of locomotives. It's also raised dilemma within preservation. For example, should English Electric Class 50, No. 50007, be called Hercules, or Sir Edward Elgar? The lovingly preserved diesel wore both names during its service life, so either can be authentic. And indeed it has worn both names during its preserved life too. But a locomotive with two names can present some fairly awkward situations. It's hard not to upset one group of devotees or another.

So perhaps the question we should really be asking, is: why give a locomotive, or anything else that runs on rails, more than one name in the first place? Especially when there's always a supply of unnamed stock, as well as a wealth of previously unused names. Why not just name something, and let it have its name for life, and if you want to fit another name, fit it to something else?...

Very much a prestige naming. Photographed shortly after the name was unveiled in October 2007, 67029 Royal Diamond shows off its fresh plates.

The answer is complex, and has to do with the prestige or suitability of the loco or train, as well as the ongoing relevance or fashionability of the name, and simply, circumstance. There may, for example, be a perceived need to maintain a connection between the train's name and its route. If the train is replaced on that route, there's a case for transferring the name to its replacement. And since privatisation, transfers of trains from one operator to another have sometimes created an immediate and obvious inappropriacy. The easy fix is to change or remove the name.

But at other times, namings, renamings and de-namings have not been so easy to rationalise as conscientious acts. It could even be said that on occasion, train operators have wanted the momentary publicity a naming can bring them, but have almost seen the name itself as baggage.

To give a sense of how fickle naming had become by the 1990s... Of the four items of motive power named between 25th February 1996 and 1st March 1996, none still retained those names by spring 1999. And you find pockets of this U-turn mentality pretty much throughout the decade. Five locos were named between 30th June 1993 and 3rd July 1993; all plates had been removed by the end of 1997. That's really not a long time for a whole sequence of namings to be undone. And as the periods of association reduce, so does the level of interest in the concept of naming.

SO DO WE NEED A "NAME FOR LIFE" POLICY?

The classic format for a naming ceremony, as witnessed at Tyesely Open Day on 28th June 2008. The loco is 47580 County of Essex.

The main problem with trying to establish a longer-term and more meaningful approach to naming today, is the evolution of culture, combined with the power of public objection in a world where social media can destroy a brand within the hour. Even if you play very safe with names and avoid potential controversy, you can still run into trouble. Are today's naming policies diverse enough, for example? And if they're diverse enough today, will they be diverse enough in five years' time? It's very difficult to mandate a "name for life" policy, with public opinion evolving as quickly as it now does - and the consequences of ignoring that evolution potentially so damaging.

Although the British Rail of the 1960s didn't exactly have a "name for life" policy, it certainly had a much greater commitment to long-term naming than the British Rail of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The story of that progression is fascinating, and raises some questions about cultural evolution that we may not previously have considered.

I'm going to start with a headline. "British Rail did not name any locomotives at all between the beginning of 1967 and the end of 1975". That's nine full years without any namings. If you don't normally go back that far with your rail history, just let that sink in for a moment. Nine years.

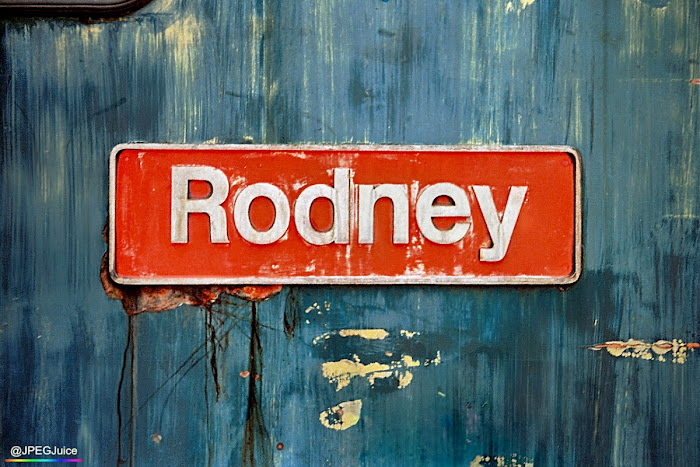

Class 50s were among the early beneficiaries when British Rail restarted its naming programme in the late 1970s. He's how 50021 Rodney's plate looked in mid 1981 after a lot of encounters with the wash.

So why did BR stop bestowing names upon their fleet for such an incredibly long time? Did someone just wake up one morning and think: "You know what?... Why bother?"?

No. British Rail was highly image-conscious in the mid 1960s. It had just revolutionised its aesthetic and was busy rolling out a new corporate Rail Blue standard, with strict design and livery application guidelines. The cessation of naming coincided almost exactly with the full go-ahead for Rail Blue repaints, and some people attribute the sudden change in naming policy to the accompanying, rather minimalistic standardisation. It's a credible explanation. But there was something else...

Military names were extremely popular with British Rail in the early and mid 1960s, and were easily the leading theme on modern traction. The 'Warships', the 'Deltics', the 'Peaks', the 'Westerns'... All heavily tributed battle-related artefacts, ranks and regiments. Indeed, the last locos to be named before BR ceased the practice in December '66, were 'Peaks' D68 and D98 - respectively christened Royal Fusilier and Royal Engineer, and continuing the military theme. Then all went quiet, and it would be over a decade before BR resumed its naming programme in earnest.

The moment that long "dry spell" began, was not just the point at which British Rail officially inaugurated its Rail Blue roll-out. It was also the point at which the 1960s peace movement really began to gather momentum in Europe. The Vietnam War was creating dismay around the world, and even veteran groups were organising high-profile protests against it. Was it still wise, in that climate, to be obsessively naming locomotives with a military focus?

The majority of the 'Deltics' had military names - Scottish for the Haymarket-based locos, and North English for the Gateshead allocation. 55004 Queen's Own Highlander was a Haymarket machine.

Was BR now caught between a rock and a hard place? If it had continued applying names, it would effectively have to take a side. Continue with the military theme and risk controversy in a culture increasingly rejecting military symbolism. Or dump its main naming theme and risk awkward questions from military supporters. A complete shelving of loco naming may have been part of the minimalistic image strategy, but it also conveniently sidestepped a political hot potato.

Whatever the real reason(s) that lay behind BR's decision to stop naming locos forward from 1st January 1967, the action itself is a historical fact. Some might argue that HS4000's appearance as Kestrel in January 1968 would count as a more recent naming. But Kestrel was really a manufacturer's type-designation. Like 'Voyager'. Just as the production models following the Deltic prototype were known as 'Deltics', any production models following Kestrel would have been known as 'Kestrels'. That's a different concept from personal, individual names like Pinza or Franconia.

STEADY THINNING OF NAMED STOCKS

In the 1970s, many of the surviving BR locos named in the '60s lost their plates, or had them deliberately removed. This included all of the Class 40s, the Class 76s, the Class 44s, and a range of Class 47s including 47081 Odin, 47082 Atlas, 47085 Mammoth, 47089 Amazon, 47091 Thor and 47538 Python.

Like all of its named classmates, 40020 Franconia had its nameplates removed in the early to mid 1970s. The de-naming was due to a demotion of the Class 40s, which took them off the prestigious expresses linked with the ship history around which their names had been themed. Subsequently, however, some of the names were restored in the DIY fashion seen in the photo above. I took the shot at Lincoln on Saturday 29th August 1981.

The reasons behind the nameplate removals varied, and included issues like irrelevance after role changes (Class 40 and Class 76), and theft-protection (Class 44). With the 47s the problem was almost certainly theft, or damage due to attempted theft. Several class members showed evidence of having their original nameplates replaced - most obviously 47079, whose name was abbreviated for the replacement fittings, from George Jackson Churchward to G. J. Churchward. Other examples had a plate on one side only - again suggesting that parties or forces other than British Rail were behind the removals.

So spotting a 'namer' by mid 1977 was a real event for the rail enthusiast. There were very, very few of them about. You were talking about 60 or so locos across the entire fleet. 'The 'Deltics', a minority of 'Peaks', and a handful of 47s. That was it. Almost...

NAMINGS RESUME

Due to the withdrawal of the 'Westerns' in the February, 1977 was the low-point for volume of named BR locos. But BR's nine-year no-naming spell had already come to an end by then. It was brought to a close on Wednesday 14th January 1976, with the naming of 87001 - Stephenson. The event was organised at the suggestion of the Stephenson Locomotive Society, who in 1975 were celebrating a century and a half since the opening of the first public-use railway - George Stephenson's Stockton and Darlington. The SLS even provided the plates.

In January 1976, 87001 Stephenson became the first locomotive to be named by British Rail in over nine years. It was renamed Royal Scot the following year, but was re-united with the Stephenson ID in mid 2003 during its spell with Virgin West Coast. Above, you're seeing the Virgin era plates, in 2003. Note that the Stephenson plates still observed the 1960s protocol of block capitals. Forward from the next official naming, this protocol ended in favour of mixed-case.

And after that? Nothing, for well over a year. The next naming was unofficial, and came when 47460 was furnished with some decidedly DIY Great Eastern plates at Stratford depot in April 1977. We can look back today and say that both 47460 and 87001 had non-standard plates. But there was no standard at the time. The 1960s fonts and plate designs had gone out of fashion, and no one had had any reason to replace them.

As a final quirk to truly end the no-naming period and herald a new era of redress, on 2nd July 1977, 87001's still fairly new nameplates were removed after less than 18 months. Nine days later they were replaced with Royal Scot nameplates. Why the re-naming? Well, the WCML's 'Royal Scot' express - powered by the nearly new Class 87s at the time - was celebrating its 50th anniversary. The new name was highly relevant. But why not fit it to a different Class 87?

Simply, historical protocol. British Rail saw the Class 87 as its new 'Royal Scot' class, equivalent to the LMS steam 'Royal Scot' class of the express's introduction year - 1927. 6100 - the numerical leader of the 1927 'Royal Scot' 4-6-0 class - had been named Royal Scot. And British Rail wanted to duplicate that protocol within its current 'Royal Scot' fleet. 87001 was the numerical leader, so, said BR, it was the loco that should carry the plates.

The Stephenson nameplates removed from 87001 would not immediately be re-used. It was another three months before, on 12th October '77, the Stephenson identity was transferred to 87101.

87005 City of London was among the first batch of Class 87s to be named in autumn 1977 when BR resumed naming locos in earnest.

And before anyone had noticed, a whole glut of "City of..." names were springing up on members of the 8700x series. Finally, British Rail were naming locomotives again. They had a new standard of nameplate design, and were setting off on a mission to make up for lost time...

In autumn 1977, the new namings progressed only through further 87s, but from 17th January 1978, the Class 50s began to join the naming schedule too.

Whilst the regiment theme had definitely gone out of the window, the Class 50s did revive the battleship theme, and a lot of the Class 87 names had military connotations too. But this was to be BR's swansong for concerted military namings. In the future, military names would crop up only occasionally on an isolated, one-off basis. The culture had changed and the public appetite was shifting towards lighter and less formal themes.

And as time went on, names would begin to cater to those lighter and less formal tastes, and even celebrate some anti-establishment figures. In 1978 when select Class 50s were undergoing ultra-formal naming ceremonies, the idea of locomotives being adorned with the stagenames of punk rock guitarists was unthinkable. But less than thirty years later, 47828 Joe Strummer, 47810 Captain Sensible... How attitudes change.

Who'd have thought it? A leading anti-establishment upstart and self-described "guttersnipe" posthumously recognised on the side of a locomotive. 47828 was named Joe Strummer whilst with Cotswold Rail. The same operator recognised fellow punk upstart Captain Sensible on 47810.

Through 1978, there were, interestingly enough, seventy-eight namings, with BR immediately moving onto the Class 86s once they'd run out of 87s. The Class 86 names incorporated a range of historical steam loco classics. Cute one-worders like Planet and Hector initially looked somewhat outrageous on modern red nameplates affixed to frontline AC electric power, but they were a refereshing departure from names you felt you ought to be saluting.

Fifty namings in 1979 was a more leisurely rate, mainly focusing on the 47s and 86s, plus the two 'Hoovers' that had escaped the main programme in '78 due to long works sojourns. And things got positively lethargic in 1980, with just twenty-one namings - although these did include the first Class 33s and 73s.

Another factor in the prevalence of naming within the passenger domain has been the switch from locomotive-hauled trains to multiple units. Many multiple units have been named, but their design makes it harder to showcase the plate than is the case with a locomotive. Here on 11th January 2001, 86205's City of Lancaster nameplate and accompanying paraphernalia shows how the space on a loco bodyside can be used to good effect. Although the info plate denotes the plaques as being added in 1993, the loco originally received the name in October 1979.

After that, naming totals per year stayed in a similar ballpark of fifty or fewer, until 1985 - which broke 1978's previous record for modern traction namings with a total of 93. And the broad trend went uphill from there. BR's volume per annum peaked at nearly 200 in 1991. But the likelihood of each 'namer' retaining its name for a full ten years had dramatically dropped. In fact, little more than 30% of the locos named in 1991 would still have their '91 identities by 1998.

THE FUTURE OF NAMING

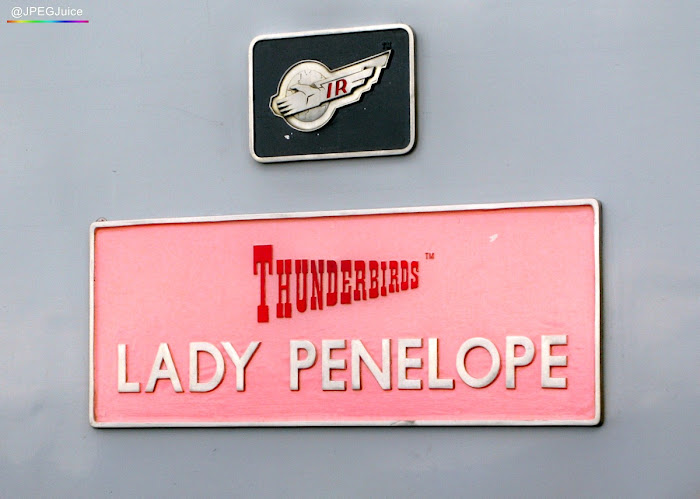

The concept of naming trains and locomotives has fantastic potential to capture the imagination. Not just of rail fans, but of the wider public. Railways are still a pretty conservative sphere of activity, but new and interesting naming concepts do emerge. Virgin Trains could be innovative with naming strategies. The graphical vinyl names were novel, and the Thunderbird theme for the Class 57s was brilliantly implemented, if not in itself a difficult connection to make given that rescue locos were already known as 'Thunderbirds'. I loved the International Rescue crests, the faithfully observed Thunderbirds typeface, and the use of a pink plate background for Lady Penelope.

Pink nameplate of 57307 Lady Penelope, with International Rescue crest.

Heading into more profound territory, Freightliner's Over the Rainbow naming of 90014, in summer 2020, was well thought out, brilliantly worded, and perfectly timed.

But looking to the future, we can probably agree that naming strategies have not come close to reaching their full publicity potential. To win new levels of publicity, names need to become bolder and more daring. Or more artistic and clever. Or radical in format - like an evolving digital display as opposed to a plate. Or maybe, in combination with the previous idea, even disposable - with a given name lasting for perhaps just one day at a time.

Much of this would contradict what we, as railway enthusiasts who prioritise the respect of the train, would want. And that shows how difficult a balance naming has to strike.

There's nothing wrong with a bog-standard, traditional naming, but even we, the enthusiasts, have to admit that so many names in the post 1985 era have proved quickly forgettable and often looked a little like naming for the sake of naming. Association is incredibly powerful in publicity, and choosing the right association is an art in itself. For train operators, it's an art worth pursuing. But there's always the nagging issue, as we saw in the 1970s, that if a nameplate, or name display, or whatever it may be, becomes too important, it becomes a major target for theft. Do we just have to accept that there's a limit to the value you can attach to the side of a train, and that we've already reached that limit?